Having recently completed DeepLearning.AI’s wonderful Deep Learning Specialization, and having recently started fast.ai’s Practical Deep Learning for Coders, I thought I would try to implement a binary classifier to test whether an image of a food item belongs to the “hot dog” or “not hot dog” class, as seen on that Silicon Valley episode.

To create this project, I used the fast.ai library, Gradio, HuggingFace Spaces, this Kaggle dataset, and Google Colab. In this article, we will discuss the notebook I used to train my model, in addition to the steps I took to deploy it. Feel free to check out the deployed project here. :)

Training

To begin, we will import any necessary dependencies.

from fastai.vision.all import *

import timm

from google.colab import drive

import osSince we are using Google Colab to execute the notebook cells, we need to mount the Google Drive to the Colab notebook’s file system. (Mounting allows one to access and manipulate files stored in one’s Google Drive directly from within one’s Colab notebook.)

# Mount Google Drive

drive.mount('/content/drive')Having mounted my drive, let’s now specify the path to my dataset directory, which itself contains two additional subdirectories: hot-dog and not-hot-dog. The former contains photos of hot dogs, the latter photos of “not hot dogs.”

path = '/content/drive/MyDrive/fast_ai_experiments/3_neural_net_foundations/hot_dog_not_hotdog/dataset/'Every image in the hot-dog and not-hot-dog subdirectories has a pre-existing naming format of “number.jpg” (e.g., “1231.jpg”). For the sake of using a better naming format, let’s use the format of “hot-dog_index” (e.g., “hot-dog_12.jpg”) for each image in the hot-dog subdirectory, and “not-hot-dog_index” (e.g., “not-hot-dog_12.jpg”) for each image in the not-hot-dog subdirectory.

# List of subdirectories

subdirectories = ['hot-dog', 'not-hot-dog']

# Iterate through subdirectories

for subdir in subdirectories:

subdir_path = os.path.join(path, subdir)

# List all files in the subdirectory

file_list = os.listdir(subdir_path)

# Iterate through the files and rename them with a numbered sequence

for i, filename in enumerate(file_list, start=1):

if filename.endswith(".jpg"):

new_filename = f"{subdir}_{i}.jpg"

os.rename(os.path.join(subdir_path, filename), os.path.join(subdir_path, new_filename))Next, we will use the ImageDataLoaders.from_name_func() method. This is a fast.ai method used for creating “data loaders” for image classification tasks; it takes various arguments, which define how the data should be loaded and prepared.

Using this method, we will define the training/validation split as 80% for training and 20% for validation; we will label each image in the hot-dog subdirectory as “hot-dog” and each image in the not-hot-dog one as “not-hot-dog”; and we will re-size each image to be 224 x 224 in pixel size.

# Creating ImageDataLoaders

dls = ImageDataLoaders.from_name_func(

path,

get_image_files(path),

valid_pct=0.2,

seed=42,

label_func=RegexLabeller(pat = r'^([^/]+)_\d+'),

item_tfms=Resize(224),

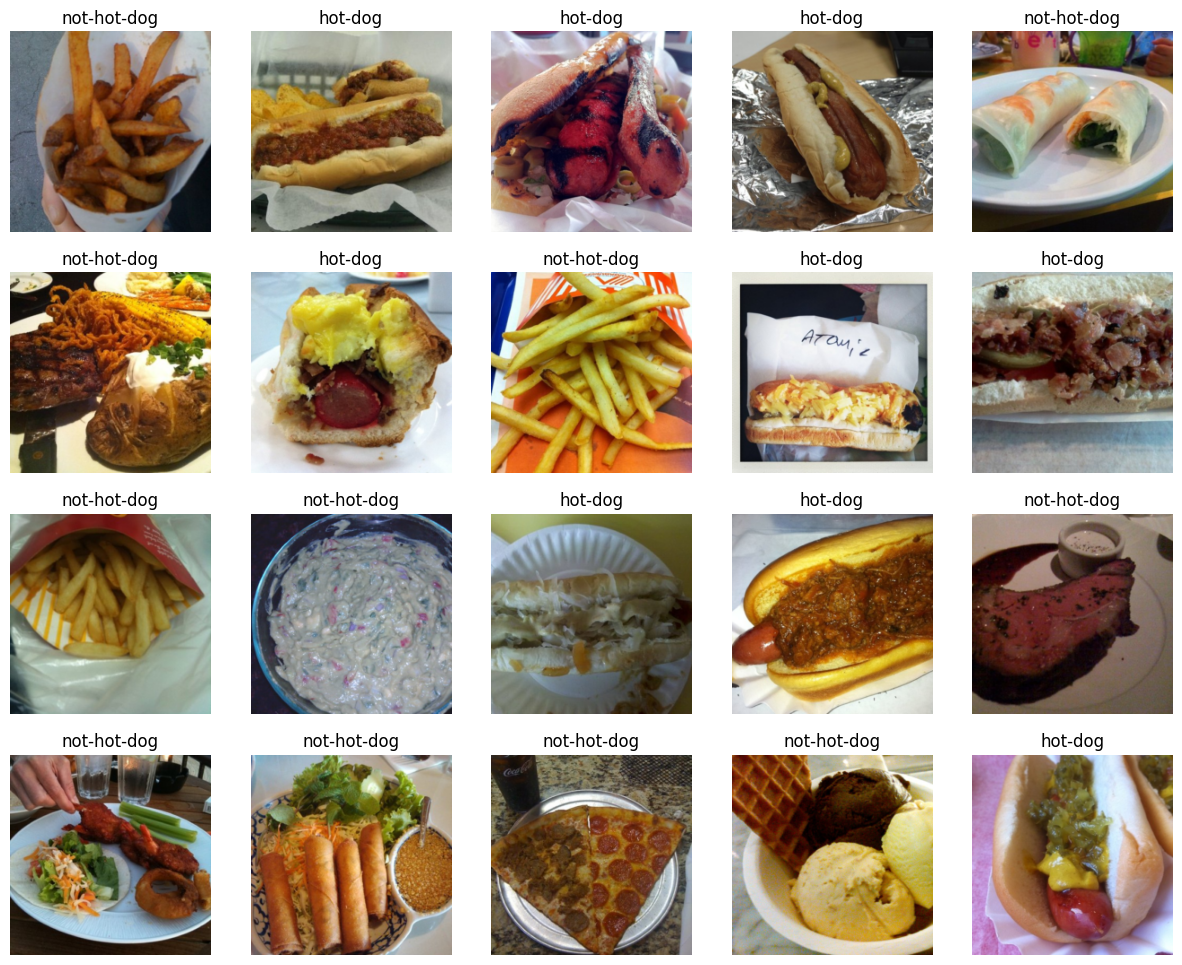

)Let’s now take a look at a batch containing 20 labeled images:

dls.show_batch(max_n=20)

Nice, it seems that each photo is labeled appropriately! Let’s now use the fast.ai library to harness the capabilities of transfer learning. We will create a learner object for image classification using the ResNet-34 architecture, train the model on our training set for 3 epochs, and then evaluate the model’s performance on our validation set using the “error rate” metric.

learn = vision_learner(dls, resnet34, metrics=error_rate)

learn.fine_tune(3)| epoch | train_loss | valid_loss | error_rate | time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.890783 | 0.328621 | 0.130653 | 02:10 |

| epoch | train_loss | valid_loss | error_rate | time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.457683 | 0.231882 | 0.105528 | 00:13 |

| 1 | 0.270772 | 0.355318 | 0.110553 | 00:08 |

| 2 | 0.187048 | 0.347728 | 0.105528 | 00:10 |

Based on this analysis by Jeremy Howard, it might make sense for us to try a different model to improve our error rate. Let’s try the convnext models.

timm.list_models('convnext*')['convnext_atto',

'convnext_atto_ols',

'convnext_base',

'convnext_femto',

'convnext_femto_ols',

'convnext_large',

'convnext_large_mlp',

'convnext_nano',

'convnext_nano_ols',

'convnext_pico',

'convnext_pico_ols',

'convnext_small',

'convnext_tiny',

'convnext_tiny_hnf',

'convnext_xlarge',

'convnext_xxlarge',

'convnextv2_atto',

'convnextv2_base',

'convnextv2_femto',

'convnextv2_huge',

'convnextv2_large',

'convnextv2_nano',

'convnextv2_pico',

'convnextv2_small',

'convnextv2_tiny']learn = vision_learner(dls, 'convnext_tiny_in22k', metrics=error_rate).to_fp16()

learn.fine_tune(3)| epoch | train_loss | valid_loss | error_rate | time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.507469 | 0.354891 | 0.090452 | 00:09 |

| epoch | train_loss | valid_loss | error_rate | time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.174055 | 0.094325 | 0.040201 | 00:08 |

| 1 | 0.131543 | 0.100523 | 0.045226 | 00:10 |

| 2 | 0.093354 | 0.084719 | 0.045226 | 00:09 |

Indeed, using the convnext models, our error rate has dropped from 0.105528 to 0.045226! Hot dog!

Let’s export the trained model so that it can be saved and later loaded for further training without needing to retrain the model from scratch.

learn.export('model.pkl')Deployment

Having created our model, we now need to showcase our project to the world at large! Hugging Face Spaces (HFS) is a platform on which we can do so. We will make use of HFS, in addition to Gradio, an open-source library that enables one to create a simple interface for a machine learning model. To see how to pair HFS with Gradio, I encourage you to check out this concise blog post by Tanishq Abraham.

Before deploying out project, we will need to make an app.py file. This file will make use of Gradio to create an interface to classify images using our pre-trained machine learning model (in this case, our model.pkl file).

Here’s my code for the app.py file:

# AUTOGENERATED! DO NOT EDIT! File to edit: . (unless otherwise specified).

__all__ = ['learn', 'classify_image', 'categories', 'image', 'label', 'examples', 'intf']

# Cell

from fastai.vision.all import *

import gradio as gr

# Cell

learn = load_learner('model.pkl')

# Cell

categories = learn.dls.vocab

def classify_image(img):

pred,idx,probs = learn.predict(img)

return dict(zip(categories, map(float,probs)))

# Cell

image = gr.inputs.Image(shape=(192, 192))

label = gr.outputs.Label()

examples = ['hot_dog.jpeg']

# Cell

intf = gr.Interface(fn=classify_image, inputs=image, outputs=label, examples=examples)

intf.launch()This code creates a simple interactive interface where users can upload images, click a submit button, and get predictions from the model. For more information regarding the project’s files, please see this link.

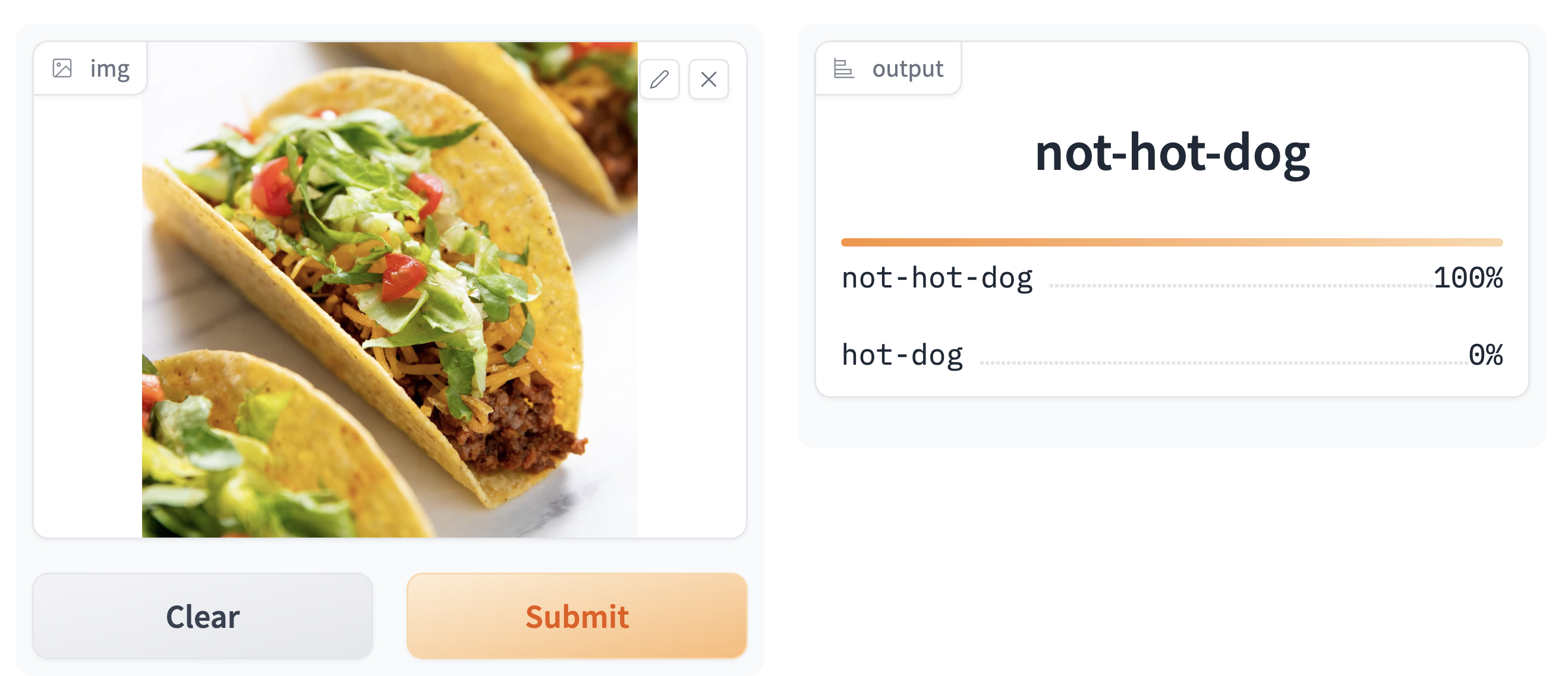

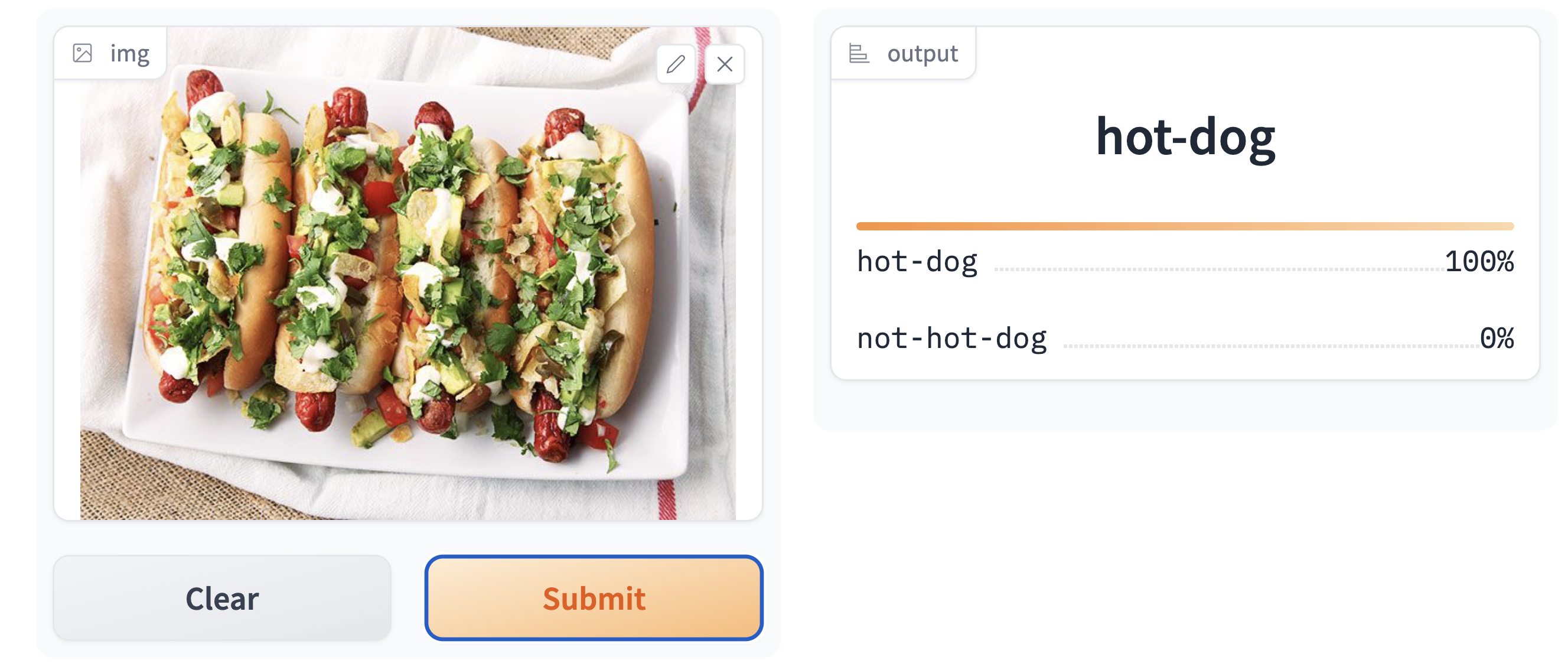

Let’s now play around with the deployed project! Let’s grab a random image of both a hot dog and a “not hot dog” (in this case, a taco).

Testing our model on both pictures, we get the following results:

Our model seems to perform exceptionally well!

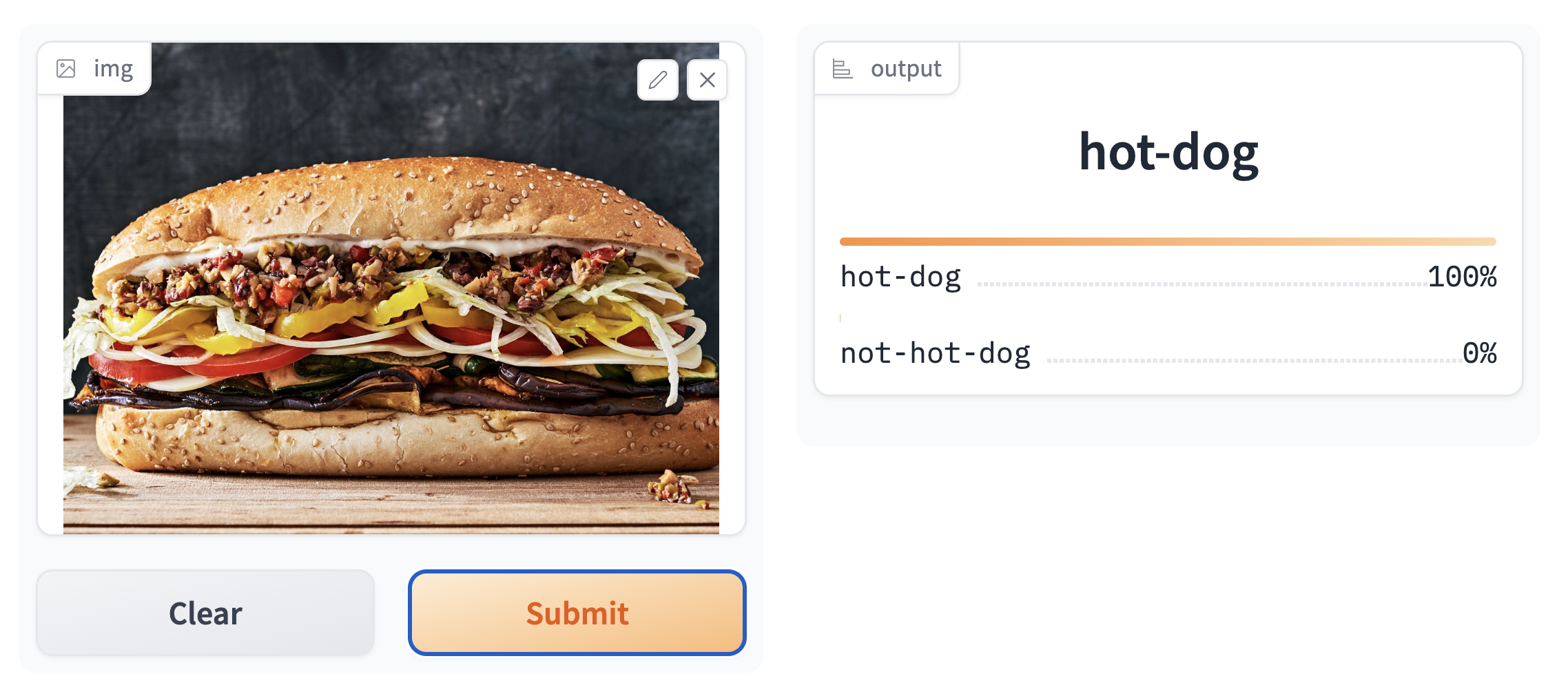

However, it is important to consider that there are still some edge cases in which the model performs rather poorly; for instance, when the structure of a food item is extremely similar to that of a hot dog…

To improve this model, we should thus try including more images of “subs” in the not-hot-dog subdirectory.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the teams at DeepLearning.AI and fast.ai, from both of which I have been able to learn a lot about deep learning in the preceding months.

Disclaimer

Some readers may wonder if a certain male appendage is able to fool this classifier. I leave all such curiosities to the explorations of the reader…